I hadn’t heard this term until I started reading about it on blogs like Cecilia Lemos’ (@CeciELT). In fact, it’s her post from November 2010 entitled Nothing More… Nothing Less… that inspires my post today. When I dug up this post, it actually surprised me how she introduced it, like admitting to being a NNEST was equivalent to facing the fact that you were addicted to a life threatening drug. Indeed, Ceci had felt ashamed, “felt less of a teacher” and “as if [she] were admitting to a flaw.” Portuguese being her mother tongue, despite years of classroom experience and learning in an English-speaking environment, it kept her feeling separated from and defeated by NESTs. What struck me most of all was this:

When I dug up this post, it actually surprised me how she introduced it, like admitting to being a NNEST was equivalent to facing the fact that you were addicted to a life threatening drug. Indeed, Ceci had felt ashamed, “felt less of a teacher” and “as if [she] were admitting to a flaw.” Portuguese being her mother tongue, despite years of classroom experience and learning in an English-speaking environment, it kept her feeling separated from and defeated by NESTs. What struck me most of all was this:

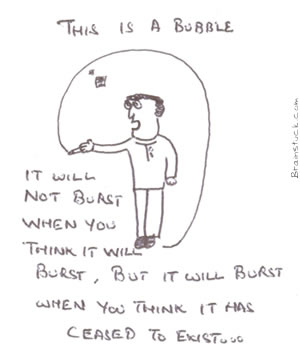

And sometimes I thought I had gotten [to native English speaking], when a native speaker – usually not a teacher – would compliment on my English, say they’d never say I wasn’t a native. That made me proud. But then another native speaker would burst my bubble by saying that I spoke English very well, but they could tell I was a foreigner. And that crushed me. Was it unattainable?

Honestly, I never really heard this sentiment so clearly through a non-native speaker’s point-of-view. Not since I was very green did I ever think any language learner would truly believe they’d completely blur the line between themselves and a native speaker. I myself have flatly said to students not to aim for being a native speaker, because by definition, they couldn’t be. There would always be something that characterises them as non-native speakers–a difference in accent on occasional words, a slightly abnormal stress pattern here and there, a tone or register peculiarity, a culturally related reference that they didn’t know. I once read somewhere that language was intentionally made difficult to master so that no matter how hard you tried, native speakers would always be able to identify their own tribes and that therefore, you were an intruder. In learning French or Korean, the road to fluency seemed decades long. Still, I never suspected my matter-of-fact-ness would burst any bubbles or crush anyone’s dreams. Having said that, is it unattainable? Yes, but for all intents and purposes, no one needs to be a native speaker, even to teach.

I’ve worked with a wide range of teachers whose native language was not English, from those who couldn’t hold a conversation with me and taught English totally in their L1, to others who showed absolutely no signs of fluency or accuracy issues, aside from one of those small inconsistencies I mentioned above. I never really questioned whether either were a good teacher though. Both had their place in the spectrum of English language teaching. The Korean private language school teachers I worked with in Seoul I believed to be best at working with beginners, teaching them the foundational grammar and vocabulary necessary to start climbing that mountain. Who better to get their students hiking up the right track? Sure, native speaking teachers are trained to work with basic beginners too, but why not utilise the cultural knowledge NNESTs have that can speak to beginners’ concerns and questions? When it comes to advanced level classes, I always thought that native speakers were the likely choice because of the nuances of the language, but only if they were trained and aware themselves. Any old native speaker wouldn’t do as is evidenced on a daily basis in classes around the world.

Of course, there’s the pronunciation concern. Should NNESTs teach pronunciation? That’s a more difficult one to be liberal about. I don’t think any generalisation can be made as NNESTs who haven’t spent time in English-speaking environments can be as unaware of target pronunciation as their students (many times, when I’ve taught pronunciation of past tense endings, for example, I’ve heard stunned students tell me that what they’ve learnt their whole lives was wrong). In other cases, NNESTs may more easily be able to relate English pronunciation to their L1 equivalents (I was so happy when I had a Japanese student show me how the /ʒ/ in casual was written in Japanese–don’t ask me right now, I’ve long ago lost it). Even some NESTs don’t always want to teach it. A previous British coworker of mine refused to spend much time teaching her students Canadian pronunciation, rightly so, I guess. I’d feel like a poser if I were teaching British English in England too. Even still, it all comes down to what the target pronunciation is and who is most capable of teaching it.

Another factor to consider is who the target audience is. One must admit that no matter how hard we try to give everyone a fair shot at a teaching position, if the students won’t get adequate learning out of collaboration with a certain teacher or there’s no noticeable difference between studying at home or abroad for the trip and money, there’s no point in hiring someone who doesn’t fit the role. If their L1-influenced accent is strong enough to make me strain to understand 100%, no matter what your experience or fluency, maybe you’re not right for a position here.

Lastly, does being a NNEST make you less of a teacher? Surely any teacher comes across words and phrases they aren’t familiar with or grammar items they can’t explain well or reading and writing microskills they need advice on how to get their students to improve upon. NNESTs aren’t alone there and certainly aren’t less of a teacher because they need to ask for help. I ask for help from them too. The reality is that NNESTs and NESTs are different and neither will ever be the other. As long as you are qualified, passionate and don’t have significant lack of any of the skills and systems of the language you are teaching, either can be effective teachers.

I’m glad that Cecilia has recognised this and I hope others do too. Your thoughts?

A comprehensive, frank and important look at a topic that comes up again and again in any framework where English is taught. I think your conclusions are “spot on”.

I particularly like your reference to the different stages of learning English. I have also found that for beginners or very weak learners the ability to understand the students’ particular difficulties is more important than other factors.

Pronounciation does seem to be the issue that parents care about most, though.

Thanks Tyson!

My own experience as someone working in teacher education and development over the years is that its most often been the “NNEST” teachers who shine brightest, work hardest, and reach for PD opportunities most. They also serve as such positive role models for their students – especially the ones who live what they teach in the classroom. This is the kind of teacher Barbara Hoskins Sakamoto and I have reached out to as contributing authors and collaborators on a course we’re currently developing for iTDi. This team of 20 fabulous (non native English speaking) teachers is by far the most impressive group of educators i’ve ever had the pleasure of collaborating with on something. The insights these teachers have is simply amazing. Barb and I (a couple of native speakers, I guess) learn so much from working with them — certainly something new every day. Of course, the teachers on this author team (which includes Cecelia Lamos by the way) are among the best of the best but they are also representative of the 1000s of wonderful “NNESTS” I’ve worked with over the years.

In the days when the very question of who is a native speaker and who isn’t (am I really after 25 years abroad?) has become so blurry, despite my use of the term in this comment, i think it’s time to put this distinction to rest. A good teacher is a good teacher. Period.

As for pronunciation, well, I did my graduate work at West Virginia University in the southern United States where I, as a New Yorker, has some comprehension issues when speaking with my “native speaking” colleagues. It’s never as cut and dried as some might think.

My favorite NNEST story comes from my own uni in Japan where one of our best Japanese (national) teachers made a speech at graduation in front of students she’d had in class variously for the previous four years. As she began speaking in Japanese a sort of gasp went up round the room and I heard a student nearby say to another student “I thought she was Australian or something like that.”

When I told this to my colleague later she said “oh really? Doesn’t make much difference where I’m actually from, does it? ” I agreed. Still do.

Hi Tyson,

Thanks for another thought-provoking read. I wholeheartedly agree with Chuck that “a good teacher is a good teacher” regardless of linguistic background, nationality and all the rest.

I have worked with some superb teachers over the years, both NESTs and NNESTs, who work hard and constantly seek ways to do their job more effectively. I have also worked with plenty of NESTs and NNESTs who are content to just go through the motions and switch off from teaching as soon as the end of the day comes. This is reflected in my PLN, through which I interact with and learn from native and non-native teachers on a daily basis. The distinction really bears little meaning to me anymore and only shows itself in the small inconsistencies you mention.

Having said all that, I do have to acknowledge the fact that I make a living off the NEST/NNEST distinction. My status as a British national means I get higher pay and more benefits than my Turkish colleagues. On top of that, I’m merely CELTA-level qualified at present whereas they have graduated from 4-year ELT programmes at Turkey’s top universities. Ask my employers why this is so and they’ll tell you two things: 1. Pronunciation modelling & 2. The students are forced to make an effort to communicate in English with foreign teachers (which is why NNESTs from places like Spain and Slovakia are employed on the same terms as NESTs at my school).

I guess that makes me a bit of a hypocrite. For all the talk of a good non-native teacher being just as effective as a good native one, I happily take the improved terms my NEST staus affords….

Hmmm…

This is a tough one, mostly because native/non-native does NOT determine whether the teacher is a good teacher or not, and yet, it does hold a lot of weight in the eyes of many.

We know what a good teacher is— someone who challenges their students to stretch themselves both in class, and then hopefully there after.

NNEST, NEST can both do this, and the good ones do.

It’s a conversation that could be continued for each context, but for me, that’s the heart of the discussion. Thanks for sharing your thoughts, Ty. Great post. Great examples. We oui.

I think we’re all in the same basic agreement in that good teaching doesn’t depend on one’s mother tongue, it depends on so many more aspects.

As far as the distinction between NEST and NNEST, I’d never qualified them that way before a year ago. Sometimes knowledge is tainting.

I’m on the same wavelength as you re: what you write about realistically attainable English proficiency for ELLs. As for NNESTs, my colleagues and I who occasionally teach ESL Part II (Additional Qualifications course) reiterate what Patricia Amato states in her textbook, _Making It Happen_, about the topic:

“Nonnative-speaking teachers need to be welcomed with open arms into teacher education programs. They make excellent role models for second and foreign language learners. Many have already successfully gone through some sort of acculturation process…and most have attained or are close to attaining proficient second language use. Because of their experience learning another language, they are generally more aware of helpful strategies, pitfalls to avoid, language learning difficulties, and the personal and social needs of learners.” (11)

Even when an NEST who has struggled to learn a language other than English has all of the above qualities, he or she may still not be as preferable a choice for employment because we need to remember that it is the pedagogical proficiency of teachers, as well as positive personality characteristics in the classroom, that will likely make the biggest impact on the success of their ELLs. Yet there are schools (I’ve heard of some overseas, but I haven’t taught there myself) that want only NESTs among their teaching staff for their EFL classes – probably because that’s what parents demand.

Thanks for publishing your very thought-provoking post, Tyson. I loved the Bob Dylan twist!

Cheers,

Kosta

As the only NEST in a school of about 10 teachers, I have first hand experience of this hierarchy of the NEST getting the more advanced students and to be honest I think that is exactly how it should be.

NNESTs can provide much needed L1 support at the lower levels of learning a language. Total immersion is a good thing but it is only the strongest of characters that can do total, total immersion and come out of it success and cheerful. Even immersion courses in a native English-speaking country will usually have one or two classmates with the same L1 and failing that a low-level learner will regularly depend on their L1/L2 dictionary, and rightfully so. All of this being the case, I tend to feel it’s better to provide these learners with a professional who has the ability to connect with them in L1 at these beginning stages.

As for the goal of passing as a native speaker, I’ve never held that up as a target me with my language learning of for my students and in fact I’ve said very matter-of-factly that it is not a reasonable goal (though Cecilia’s comments about ‘bursting the bubble’ will make me reconsider this approach the next time the matter comes up).

The problem is that a lot of students I’ve encountered tend to equate pronunciation with accent. Very few native speakers can effectively adopt another accent (though we do see it with actors helped by dialogue coaches I suppose) but variation in native accents is accepted and indeed celebrated in most languages.

On this point I defer to Adrian Underhill who, in his excellent pronunciation workshop for Macmillan, encouraged us to celebrate the differences in pronunciation among different learners. The French accent of a CEFR C2 speaker of English is, by definition, fully comprehensible yet still immediately identifiable as French. Variety is the spice of life and we shouldn’t all be aiming for just salt and pepper!

Not confident with my HTML tags so here is the plain link for Underhill’s seminar – http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1kAPHyHd7Lo

Some very good points, Gordon. Thanks. I wholeheartedly agree that a comprehensible fluency by any learner shouldn’t necessarily be ‘taught out’ as it were. What difference does it make if a student has a French, German or British accent? Everyone just needs to accept it and in Toronto, I think the majority of people do considering its immigrant population. Having said that, if said accent precludes them from work in their desired industry (unreasonably), I can see why accent training may be a desired outcome for some learners.