For some time, I’ve been increasingly feeling like we suffer from the warm, fuzzy, everything-is-wonderful syndrome. We pat each other on the back when it’s deserved, but also when it’s not, and though this accomplishes what it sets out to–we feel good about ourselves–it also breeds mediocrity. This spills over into our classroom philosophies as well. Are we really helping our students achieve their potential with language or are we unintentionally filling in the gaps and overlooking errors they make because comprehensibility alone is the goal? I subscribe to Underhill and Scrivener’s Demand High ELT, which looks at “ways of getting much greater depth of tangible engagement and learning” and in a recent conversation with my colleague, Katherine Anderson, she reminded me of a great activity that pushes students to be better.

Do you ever think about how much you learn to understand the way your students communicate? There are a lot of times that we are overly forgiving of what our students say or write because we know what they mean. It can come to a point where we regularly accept the wrong word, collocated phrase, or grammar (and have you ever found yourself actually making that error yourself in their presence?). Try turning the class around and having students tell you what to do. The twist is, do what they suggest literally. They’ll quickly come to realise that not everyone is going to be so forgiving.

Literal instructions example

Because my classes could be in any building throughout campus, available technology in the classroom itself is a crapshoot. Some have ceiling-mounted projectors; some have smart consoles connected to the internet; some have nothing but a blackboard. More often than not, it’s the latter. In these cases, I need to carry a projector, laptop, extension cord and speakers to the classroom. Though I’m rather adept now at hooking it all up within a few minutes, why not turn it into a high demand communication exercise?

Plop all the equipment down on the desk and ask students to tell you how to connect it all together in order to watch clips of a TV show or movie for the lesson. It, however, depends on students instructing you on exactly how to do it. Keep in mind, you must do exactly what they suggest.

Students: Open the laptop and turn it on.

Teacher: OK. But it won’t turn on.

Students: Put the electricity into a wall.

Teacher: I’m not an electrician. I can’t do that.

Students: Hmm. Put the string into a wall.

Teacher: The string? <You pull a string from your clothes, for example, until students realise that’s the wrong word.>

Students: Cord. Bring up the cord into a wall.

Teacher: Oh. Bring up the cord? <Point to the cord and speak to it kindly> You’re a good cord. Do you want to be a good wall one day? You have to practice really hard at being flat and solid.

Students: Plug the cord into the wall!

Teacher: Oh! <Plug the cord into the outlet.>

You can see what I mean here. Often for time’s sake, we forgive the incorrect language our students use because we know what they mean. Depending on the task, this can give them the impression that what they use is acceptable, a false security they may quickly realise when frustrated communicating outside the classroom. It’s about helping learners realise that are capable of producing better language for context and comprehensibility. It’s about our realising that overlooking their errors is actually a detriment to our students’ progress.

Keep in mind that the vocabulary and grammar required in the task should have been earlier taught and practised. Keep in mind that it’s not aiming to be impossibly difficult.

In the end, students will get a little frustrated, laugh and push themselves to try harder. Plus, who doesn’t think trying to bring up a cord to be a good wall is funny? =)

I like it. I’ve been there. I carried video players a lot and those allegedly portable OHP suitcases.

I love that activity, very good for describing processes and showing students their weaknesses. They need the language to do something and it becomes very clear when they don’t have it. I use a similar management simulation with different levels of hierarchy giving and following orders.

Yes, we are too soft but I’ve never liked it and so have always had a bit of a reputation for being tough or ‘demanding’. I REALLY hate all that “oooooorrrr” rubbish. And talking about students like they’re babies. I also hate teachers talking down to their students or laughing about them. Low level does not = stupid. Any student above 18 is an adult and should be respected but challenged. I’ve had many who ask “why?” and lots of questions because they want to improve, they don’t want “it’s OK”. Others notice when you let things go and ask. They think you’re 1)lazy or 2)have poor English and don’t notice the errors. I had a colleague like that who was tooo friendly and her class revolted and said her English level was too poor to teach.

Now I’m not saying cane the students but push them and if they have problems help them a bit. No spoonfeeding with constant support and handouts. Get them to do stuff on their own. I often say “X I think you have a problem with….work on it over the weekend and tell me how it went on Monday”. This means they need to use their grammar/vocab…books/sites. A lot of students say “nobody’s ever said that to me before” and initially are shocked but I say that I’m honest and that’s what they need to do, after all, they are adults.

You’re right – students crave correction. Students deserve to be told that they need to work on this or that area. Students are often babied too much. It’s one lesson in this EAP program I work in that I learned early on: don’t spoonfeed them because if you do, they will be in for a rude awakening during their first year.

Still, it’s not about discouraging either. We do need to foster an environment where students are willing to take risks with what they’ve learnt. It, however, is our job to not allow those risks to fossilise if wrong.

I like doing this kind of thing, not out of any desire to push my students harder but simply because it appeals to my sarcastic side. A common transference issue with Turkish students is the use of ‘open’ and ‘close’ when ‘switch on’ and ‘switch off’ are needed. So, when a student suggests I ‘open the light’, you’ll often find me standing on a chair underneath the bulb looking for some kind of handle. More often than not, that leads to someone producing the correct ‘switch on’ form (also adaptable to computers, projectors, telephones and cameras).

I’ve also applied the ‘literal meaning’ tactic (with a dollop of sarcasm on the side) when students are mixing tenses (e.g. Me – ‘How was your holiday?’ Kid – ‘Great! I am in America’ Me – ‘Is this a hologram call?’ ;-)). Far from being traumatised, they find it funny and it usually leads to self-correction/clarification – always desirable.

Haha, Dave! I completely get the sarcasm angle you approach this activity at! I’m sure that this activity appeals to that side of me as well, being a lover of dry humour myself…

I loved the post, and it really struck a chord with me. I have this one student, in particular, who loves to say “you know what I mean, teacher” every time she states something in class (errors included). And of course, most of the time I do, and eventually let it slide.

I’ll be considering this with greater care, and looking at ways on how to create greater awareness of how important it is to work harder, in order to achieve more. Excellent idea on plugging in the ‘electricity’. 🙂

Cheers.

It’s very easy to let it slide, Lu. I do it. Your colleagues do it. You do it. We all do it sometimes because it can be easier than trying to reexplain things over and over. Of course, flipping the instructions this way tends to drive the point more home to students. Let them try outside of class and they’ll realise not everyone knows what they mean.

Great approach. It works for more than English — I remember a similar tactic used by a computer programming instructor. He required the class to give instructions on how to make a peanut butter and jelly sandwich; he had come prepared with the ingredients, and proceeded to follow all instructions literally. Quite a mess. And a very memorable lesson.

I can see this being useful almost anywhere, particularly in TESL classes too. New teachers tend to explain things poorly, simply because they aren’t in the habit of doing so to our audience. Simplifying verbose instructions is an acquired skill, obviously not only for language teaching.

This discussion has also reminded me of an activity I used to use when teaching adults designed to get them to pay more attention to instructions (I take no credit for it – I found it in a book and I’m sure you’ve heard of it before 😉

The whole thing sentred around the first instruction which said something like “Please read all of the işnstructions carefully before you do anything else”. There then followed a series of increasingly bizarre instructions (“stand up and turn around three times”, “shout out ‘I love English!'” and so on) before the last one said “Now that you have read all the instructions carefully, give this paper back to your teacher”.

They hated me when I told them they were only supposed to read and not actually do any of that stuff!! I should use that with my young learners once school starts again 🙂

Hahaha. It’s almost a Simon Says in a way.

This is something which resonates with me. I gave a talk at IATEFL 2012 called the Se7en Deadly Sins of ELT in which one of the “sins” I attacked was the common feeling that telling learners that what they just said was “wrong” in some way was to be avoided. So when I saw JIm Scrivener and Adrian Underhill debuting DHT I felt like a general tide was turning and a few of us were catching the same wave, so to speak.

But in particular your post makes me think of Long’s interaction hypothesis, the reworking of Krashen’s input hypothesis, which suggested that morphosyntactic development occurred as a response to negotiation for meaning (by which he meant those moments when communication breaks down due to ambiguity and speakers are forced to resort to greater precision – and as a result need to leverage greater grammatical accuracy – in order to get the job done.)

The problem with this idea – which has gained currency in ELT circles, as Krashen’s ideas gained currency before it, despite their being demolished by linguists at large, is that – surprise, surprise – learners don’t resort to the kind of negotiation for meaning that Long’s hypothesis depends on. Classroom research by Foster, Foster and Skehan and others have reliably shown that such negotiations that do occur rarely if ever hinge on morphosyntax, and often are lexically dependent. Further, what more often happens is that learners scaffold – or accommodate – the interlocutor’s weakness. In other words, they do what normally socialised humans do – they collaborate.

So your idea of “playing things literally” is a fun way of overriding this natural human trait and thus allowing a chance for Long’s hypothesis to operate. Time will then tell whether such negotiations actually bootstrap general performance over time.

Hmm. I haven’t heard of Long’s interaction hypothesis though it would make sense if I just heard it out of the blue. I can see how in actuality, listeners and speaker negotiate together to understand meaning. Of course, this assumes that the listener gives the speaker the time of day. Not everyone is so patient.

All in all, I believe the tide is turning in certain circles towards what you, me, Scrivener and Underhill are starting to propose. Check out some of the comments in Ceci’s post for example: http://cecilialcoelho.wordpress.com/2012/06/03/hi-my-name-is-cecilia-and-i-am-a-recaster/#comments =)

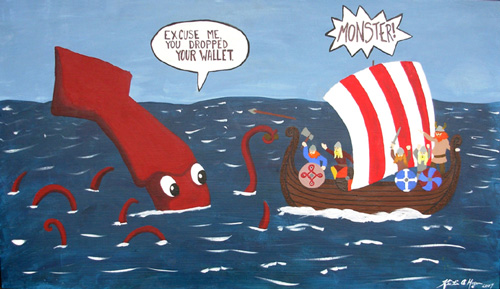

One could extend this to drawing images of what a student is saying. For example, they say ‘I play IN a guitar’. You retort: ‘that’s a problem’ and draw a tiny figure inside a huge instrument. They laugh and correct themselves: ‘play ON a guitar’. You respond: ‘poor guitar!’ and draw a figure literally sitting on the instrument. They’ll laugh again and work a bit harder to arrive at something less damaging for the player and the instrument.

Sure, Nastya. Sounds like a great variation of the idea.

I agree with you Tyson with a caveat. As you know from my blog, I’m not scared of making my students work, both in terms of effort and the thinking involved, and like you I don’t like to let mistakes slide just to make things easier.

The activity you feature above is a fun way of making the students really think about what they are saying, but I think it has to be carefully executed. You need to have a pre-existing good relationship with the students so they trust you and will allow you to push them. And I would worry about it going on too long. If not carefully managed, it could become irritating for the students.

You say at the end “who doesn’t think trying to bring up a cord to be a good wall is funny?” and I think the answer is not many people, but still some people nonetheless. I imagine my old Portuguese teacher used to think a similar thing about playing pop songs in the lesson. “Who doesn’t enjoy singing along with music” she might have asked herself. Well, the answer was me, for various reasons I found it annoying, pointless and frustrating.

So in short, I do like the activity and the ethos behind it, but I think it needs to be carefully carried out.

Good points, James. Execution is important as with all tasks. You do need to know when to help out and when it’s just not going anywhere. I’m not sure I’d equate the general enjoyment of humour with the love (or lack thereof) of singing along to pop songs.

But you didn’t mention the general enjoyment of humour, you mentioned a specific example! You’re probably right, most people would find it funny, I was just trying to offer a warning that often things we think are universal are not as popular as we think. But it was just a small point and shouldn’t detract from the main point that the activity is an example of a very appropriate shift in the right direction.

Right, key word: example. ;P Haha, in all seriousness, you’re totally right. We can’t assume everyone likes everything we like.

[…] Literally following instructions – We pat each other on the back when it’s deserved, but also when it’s not, and though this accomplishes what it sets out to–we feel good about ourselves–it also breeds mediocrity. (Seburn) I feel like we’re sometimes a little too supportive of each other, aiming to not even be constructively critical. And this made me wonder if we are too forgiving of our students mistakes too, not pushing them enough. […]

[…] Share fourc.ca 5 months […]

Just checked into ELT mob after ages and saw your post.

Jo Watson described to me a similar activity once for pre-service teacher training to try to get trainees to give clear, concise instructions. Something like, ‘instruct me how to put on my jacket’, and then go along the same bumbling, literal route.

I had completely forgotten about it, but will try to give both your and her activities a shot and see how it goes.

Thanks for the comment, Ben. I had nearly forgotten about this post. I don’t think I really know what it means to check into ‘ELT mob’. 😉

I think this activity isn’t so unique, but one thing that can be quite useful is using IKEA instructions as a starting point. How many of us can relate?

Hmm, well that’s where I saw the summary of your idea! http://linoit.com/users/annaloseva/canvases/flashmobELT

Will definitely dig out an old ikea manual or two.

Ohhhhhhhhh! Now I remember putting this there. 🙂 While you use the IKEA manual, why not get the students to build something for your classroom while they’re at it. 😉

Hmmm, I am expecting a baby in a couple of months – I wonder if they could put together a crib?

Perfect!